Nancy Nix

Founding Director—TCU Neeley Center for Supply Chain Innovation / Executive Director Emeritus—AWESOME

Admittedly, it took Nancy Nix a while to catch on. Life growing up in Nashville, Tennessee, was somewhat sheltered. For many years there was no TV, and of course at that time no internet. Their father, a postal clerk, was a stern disciplinarian to his five kids. Their mother focused primarily on being a homemaker when they were young. “I didn’t have a way to learn much about business or the way the world worked,” she says. In other words, life was local and lived up close. Or, as Nancy’s brother put it, “How in the name of God did all seven of us exist in that tiny house with one bathroom?”

Still, Nancy learned things that would help her embrace the world. As a leader, teacher, and supply chain guru, she developed a global perspective on how to get things done and has imparted that knowledge to thousands of students and colleagues. In doing so, she’s shaped the present and future of the global supply chain—which means she’s shaped the world in which we all live.

“I don’t know,” she laughs. “Maybe I said ‘yes’ too many times. My career went everywhere.”

The third of three girls in her family, Nancy was the shy one. She was an athlete who read voraciously and played the piano for hours. She was also a gifted student in math and science. When it was time to go to college, Vanderbilt University awarded her a full scholarship.

“My parents worried that people were going to take advantage of me,” says Nancy. They needn’t have. When Nancy learned three weeks before starting college that Vanderbilt expected her to live at home and commute instead of living in the dorms, Nancy picked up the phone and called the University of Tennessee. She hadn’t even applied there, but she asked to be admitted. Tennessee looked at her test scores and her intention to be a chemical engineer and gave her a place in the freshman class…plus a full scholarship.

Nancy was figuring out how the world works.

College was fun—maybe too much fun. The summer after freshman year she met another student while working at DuPont. “With the infinite wisdom of a 19-year-old, I decided to quit school and get married,” she sighs. “I told you I was naïve, right?”

While her husband stayed in school, Nancy worked. Then babies came. She tried settling into life as a mother and the wife of a DuPont man, but Nancy was restless. Almost ten years after she left college, she re-enrolled to finish her degree.

The days were long. She was a wife and a fulltime student and the mother of young children. She studied early, or late, usually while her little ones slept. But she finished with a degree in Chemistry. And then she, too, went to work for DuPont.

Her initial job was as a first line supervisor on rotating shifts in a facility that spun nylon yarn. Tensions at the plant were high after a bitter struggle between labor and management years before. Nancy’s team tested her: They sabotaged her spinning machines, first dumping water on her head, then putting dye in the finish tanks and ruining $30,000 worth of yarn. She wondered sometimes if she might be assaulted leaving the plant at midnight after the evening shift.

“When I started, I wasn’t exactly young, but I was just a college grad who didn’t know anything about the business,” she says. “I had an all-male crew in an area with no other female supervisors. They made it a little rough for me. But I learned a ton.”

Leading meant mastering what her employees had to do so she could understand: Capture hot nylon as it was extruded and wrap it around 18 winding tubes without breaking it. She stayed unflappable and earned respect. DuPont noticed and promoted her.

If Nancy’s star was rising at work, though, it wasn’t at home. Her marriage foundered as her career took off. When DuPont gave her a new role, she took herself and her young sons 700 miles away to a city where she didn’t know anyone. There she met her second husband, “at the coffee machine, basically,” she says. When they decided to marry, there was just one problem: He had just been promoted to plant manager and DuPont didn’t allow employees to have a spouse for a boss. The ultimate solution was for Nancy to move into a separate division—contracted distribution and procurement. And her career in supply chain began.

She was a good fit for the role. DuPont moved her through several managerial positions in manufacturing, logistics, procurement, and customer service. She led a team that developed an integrated procurement and logistics strategy across Canada, the U.S., and Mexico. She also worked in a corporate planning group where she facilitated strategy, development, and sales training sessions with DuPont’s global business leaders. During that time, she also completed her MBA at Temple University. Her global perspective was growing.

Then she and her husband had the opportunity of a lifetime—to go to work as joint VP of Logistics for Reliance Industries Ltd. In Mumbai, India. Their job was to help build a new polyester fiber manufacturing facility. As joint VP of Logistics, Nancy focused on helping to strengthen Reliance’s logistics processes and planning.

“That was when I really began to understand and appreciate the global environment,” she says. She was living and working in a different country and culture, halfway around the world from family and friends in a time without email or internet. “We had a fax machine, and we could fax the kids if the construction crews didn’t cut the phone lines that day. Half the time, though, the phone lines were down, and you couldn’t even fax.”

When her father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, Nancy came home. Her husband stayed in India and for a while they commuted between Knoxville and Mumbai. “That was long,” she says.

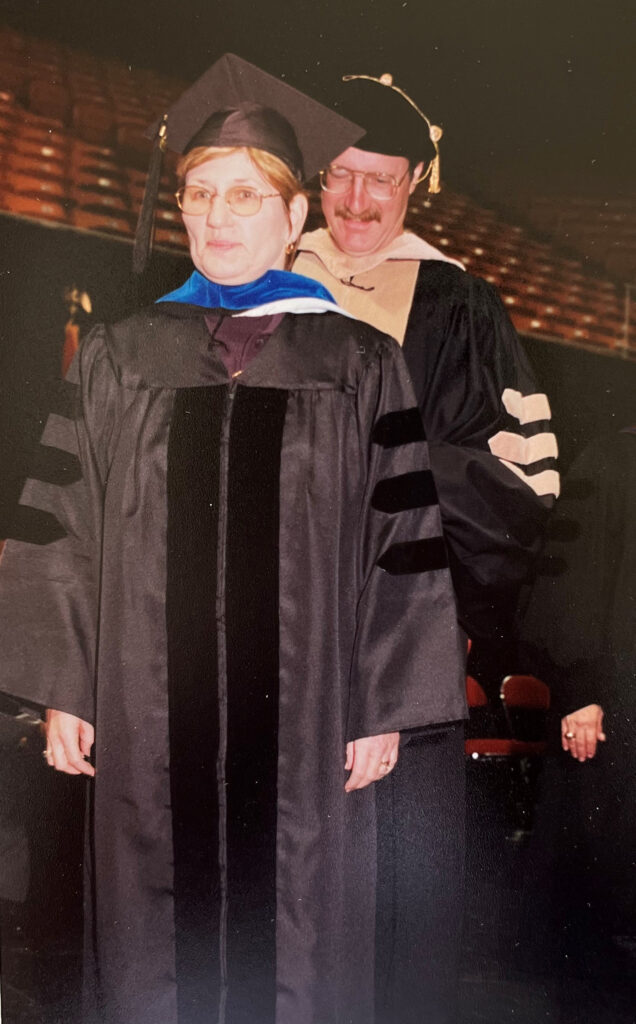

It was a time for redirection. Nancy went back to school, this time for a doctorate in Logistics and Marketing from the University of Tennessee. As she finished, Texas Christian University (TCU) hired her to establish the Supply Chain and Value Center at their M.J. Neeley School of Business. For the next eight years, Nancy both taught and built the center into a significant area of focus at Neeley. She developed programs, raised funds, and brought in corporate sponsors and advisors. One of her innovations was her emphasis on a global curriculum, including study abroad programs for students designed to broaden their perspective. For her many innovations and contributions, TCU recognized Nancy with their Outstanding MBA Faculty and Curriculum Innovation Award.

She stepped up next to become the Executive Director of the EMBA program at the Neeley School of Business at TCU. When she stepped down from that role in 2013, it looked like Nancy was finally heading into retirement.

But life had other plans for her. AWESOME—Achieving Women’s Excellence in Supply Chain Operations, Management, and Education—launched in 2013, right as Nancy was wrapping up at TCU. Nancy became the founding Executive Director of AWESOME, responsible for all areas of the organization. Under her leadership, AWESOME membership grew to more than 1,000 women in senior leadership roles in supply chain. Nancy also helped initiate the annual AWESOME Symposium, the AWESOME/Gartner Women in Supply Chain research, and the AWESOME Excellence in Education scholarship program.

Today, she is Executive Director Emeritus at AWESOME, still guiding and advising the organization. And her influence continues in other ways: Her articles have appeared in the International Journal of Logistics Management, the Journal of Operations Management, the Journal of Business Logistics, Supply Chain Management, and Texas CEO Magazine. For several years, Nancy served on the board and on various committees of the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP). In 2017, CSCMP honored Nancy’s accomplishments with their Distinguished Service Award.

“I think the journey’s been about taking on new things and learning,” she says. “I tell women: Be willing to do the dirty jobs. Do well at them. Work hard. That earns you all kinds of credibility. And don’t just focus on getting the job done. Think about how you can make things better.

“Early on,” she says, “I was afraid of failing. And then I got that I was never going to be perfect and it was all just an opportunity to do my best and move on. We’re all in this together. How do we work together to solve a problem? That’s where I think we always need to start. And what do I regret? I can’t think of one thing.”