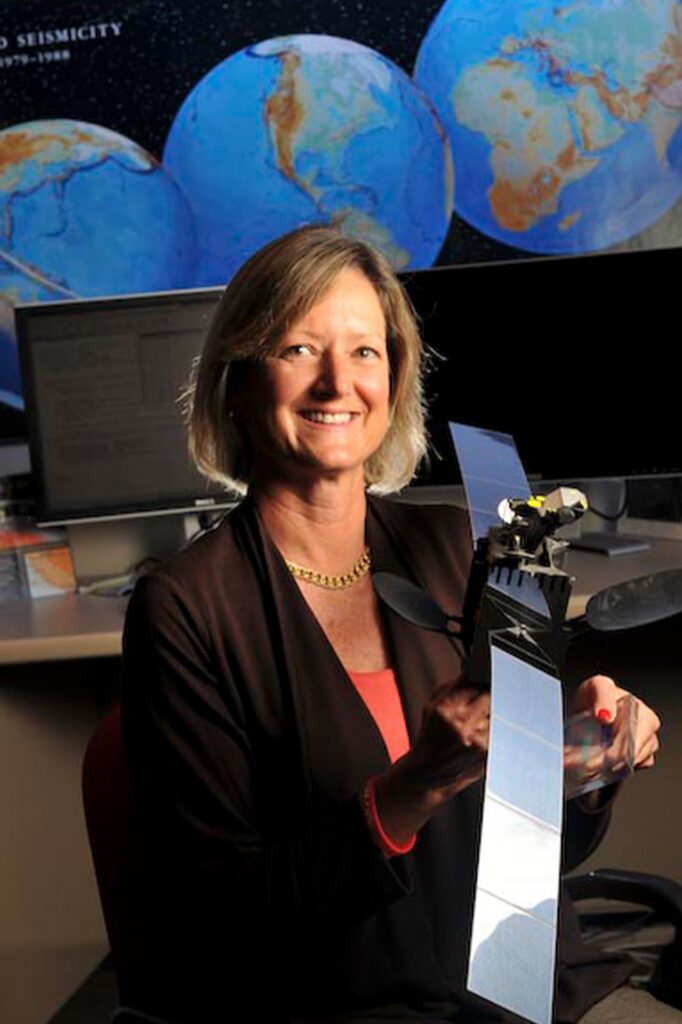

Celeste Volz Ford

Board Chair and Founder, Stellar Solutions, Inc. / General Partner, Stellar Ventures

In high school, Celeste Volz was one of the lucky ones. “I went to a high school that was really strong in math and science. That made me strong in math and science,” she says—as a girl, an advantage right out of the gate. Then people told her, “You should be an engineer.” Celeste didn’t understand then that girls who are gifted in math and science aren’t always encouraged to enter technical fields. She took it for granted she could become an engineer if she wanted to become an engineer—and if someone could please just explain what engineering actually is. “I even talked to a couple engineers and I was still confused,” she admits.

Then she opened the catalog for the University of Notre Dame, where she was headed in one of the first classes to admit women. Her eye fell on a subject—Aerospace Engineering. She liked the idea of studying something different. What she didn’t know was that NASA was in a hiring slump; demand for aerospace engineers had cratered after the space race of the Sixties ended. She signed up for class and noticed her first seminar had “like, seven people” in it. All were men.

It was, it turns out, a great time to become an aerospace engineer.

If the era of lunar missions was winding down as Celeste went to college, the era of satellites was ramping up. Countries were discovering that satellites could track weather, boost communications, ease navigation, spy on neighbors, and much more. By the time she graduated from Notre Dame, Celeste and her classmates were getting wined and dined by agencies hungry for aerospace engineers. She stepped out of the classroom into her first job at COMSAT, the private communications satellite corporation created by Congress.

Satellites are “little followers,” as their name suggests, although no one quite knows where the word came from. There are natural satellites, like the moon, faithfully tagging after earth as we circle the sun. And then there are artificial satellites hurled into space to do our bidding. A satellite constantly wants to tumble to earth in a fatal embrace. What keeps it in orbit is precisely the right velocity and directionality to counter the siren song of gravity.

Managing that balance was Celeste’s job as a guidance and control engineer for COMSAT. But she was an anomaly. Most of her colleagues were grizzled aerospace veterans. Worse, part of the reason she was brought on board was because Washington told the Palo Alto office to start hiring people straight out of school. “That’s stupid,” the Palo Alto team told Washington. They hired Celeste anyway.

“They had low expectations of me,” she admits. On launch days, she was aware of being the only female voice in Mission Control, “a very large room,” she remembers. “And I realized that if I said anything wrong, everyone would know who said it.”

Being the only female also worked to her advantage, however. “It meant people noticed when I spoke in a meeting and remembered what I said. And that was uncomfortable, but it was also really good.”

It didn’t hurt that she had bosses who believed deeply in her and were hellbent on seeing her advance. She also worked her backside off. Shortly into her stint at COMSAT, Celeste enrolled at Stanford to earn a master’s degree in Aerospace Engineering. There, she learned about non-linear control systems and brought that back to her colleagues at COMSAT. They’d never seen the algorithms Celeste was modeling. But they were impressed, and her reputation grew.

From COMSAT, Celeste moved to Aerospace Corporation as a project manager, where her work on NASA’s Space Shuttle Program led to recognition as “Woman of the Year.” For 17 years, she calculated orbits and managed satellites at different firms. Then, at age 39, Celeste launched Stellar Solutions in 1995, an aerospace engineering services firm serving defense, intelligence, commercial, civil and international clients.

She was also married and launching new lives. Celeste started her company while running a household with three small children in it. Sometimes she wondered if she should be home with her babies; it was what her mother had done.

“My mother was so engaged with us,” says Celeste, “even though she’d been to law school and could have become a lawyer. She encouraged us to try everything. I think my belief that I could do anything really came from her, because she gave us the sense that we were amazing.”

So, Celeste made a choice. “I thought, if I’m going to leave my kids to go to work every day, it better be a great job where the work is important and high impact,” she says. And she wanted all her employees to feel the same way. She’s succeeded; since 2014, Stellar Solutions has been regularly named to lists of “Great Places to Work” by Fortune Magazine and others. Interestingly, among her hires were the first two bosses she ever had; they now work for her. She also has a staff where more than half the leaders are women.

She’s accrued other honors as well. Under her guidance, Stellar Solutions earned a Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award and the California Award for Performance Excellence. Celeste has personally won a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Baldrige Foundation and the National Association of Women Business Owners. She’s in the Silicon Valley Engineering Hall of Fame. Ernst & Young named Celeste its “Entrepreneur of the Year” in 2009 and the National Defense Industry Association has called her its Small Business Executive of the Year.

Celeste is also a member of numerous public, private, and nonprofit boards, including the Board of Trustees at the University of Notre Dame and the Council on Foreign Relations. She is an Associate Fellow at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. She’s been on the Enterprising Women Advisory Board to support national/international entrepreneurial mentorship since 2020, and she’s also served on the Board of the California Space Authority.

In 1998, Celeste established the Stellar Solutions Foundation and in 2001 the QuakeFinder humanitarian research project. QuakeFinder operates a network of sensors in earthquake-prone areas that capture data on ultra-low frequency electromagnetic emissions. Such data can help predict potentially disastrous seismic activity. Most recently, Celeste launched a new company called Stellar Ventures, a venture capital firm focused on investing in the next generation of space technology firms. “I couldn’t believe how few women are funded by venture capital,” says Celeste, “and how few women do the funding. So, I thought, ‘Here’s an industry where we need to step it up.’ Because for women in space, the sky’s the limit.”

The one thing missing from this picture of achievement is the person who inspired Celeste in the first place. Celeste’s mother died while she was in college.

“I think she must have been brilliant,” says Celeste. As she and her sister approached college age, tuition money was tight. So, Celeste’s mother—after staying home with children for 18 years—dusted off her law school texts and prepped for the bar exam. “And she passed it,” says Celeste. “I mean, who does that? Who teaches themselves law school in two years? But she did, and she went back to work for us.”

“I still carry her inside me because she was such a role model. ‘Believe in yourself,’ she taught us, ‘and anything’s possible.’”