Carol Ross Barney, FAIA

Founder and Design Principal, Ross Barney Architects

To create something that distills everything human, imagine a city. To imagine a city that makes everything human better, create Carol Ross Barney. “Cities are where we are our most creative, the most energetic,” says Carol. “Cities are dynamic. They’re powerful.”

Cities are an amazing, relatively new technology that humans came up with to encourage commerce, culture, and community. They also incubate poverty, disease, and hurt. And, in this modern world, they contribute hugely to climate change and climate crisis. The difference between wholeness and distress lies in how they function.

For half a century, working as an architect, Carol has dedicated herself to “the dignity of design”—defining urban spaces (both grand and workaday) that make it easier to be a good human. She’s been passionate as well to creating cities that are resilient and sustainable now and in the future.

“Our premise is that design matters—all the time,” says Carol. “Good architecture shouldn’t be a privilege just some people get. It should hold cities together and make them more livable for everyone.”

It’s an ethic that’s earned her the nickname “the People’s Architect.” It’s also taken her to the top of her profession. Chicago—where Carol grew up—is the city that’s most felt her touch, although she’s completed important commissions in Oklahoma, Cleveland, Arkansas, Duluth, and more. In 2023, the American Institute of Architects honored her with their top prize, the Gold Medal, for being someone “whose work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture.” That gold medal joined more than 200 other major design awards that Carol has won in her long career.

But Chicago is where she has been able to manifest her belief in the transformative power of well-designed spaces. Indeed, it’s hard to travel around the city and not encounter her work: The Chicago Riverwalk, the Searle Visitor Center at Lincoln Park Zoo, the Chicago Cultural Center, McDonald’s Global Flagship restaurant downtown, the CTA stations at Cermak/McCormick Place and at Morgan Street, the Multi-Modal Terminal at O’Hare, and (in 2026) the new DuSable Park overlooking Lake Michigan. To say thanks, the City Council proclaimed September 14, 2023, as Carol Ross Barney Day in Chicago.

Not that every assignment has been glamorous. “Oh, we’ve also designed chillers and substations and utilities,” Carol laughs. In the city that works, good design is just as important for what she calls “the interconnective tissue —the stuff that’s in the cracks and crevices at the edges—that hold cities together.”

As a girl, she always liked to build things and to draw. “The joke in our family was that if something was broken, give it to Carol to fix,” she laughs. The oldest of eight born to first generation Americans, there was never any question that Carol and her siblings would attend college and succeed. Furthermore, she was inspired by President Kennedy’s imperative to “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” At Regina Dominican, her all-girl Catholic high school, Carol told her college guidance counselor that she wanted to be an architect because “just painting didn’t seem like enough.” Sister Catherine Patrick never told Carol that an architecture career was a long shot for girls in the 1960s. “I’ll see what schools I can find,” she told her.

The University of Illinois was where Carol landed. “That’s when I found out there weren’t many women in architecture,” she says. Out of 312 students in her freshman class at architecture school, 12 were women. Five years later, only 100 of that original class graduated with an architecture degree. Of those, three were women.

Carol almost wasn’t one of them. She failed a design course her first semester. “My teaching assistant told me he didn’t think women should be architects,” she remembers, “and he flunked me. The dean of the college magnanimously changed my ‘F’ to a ‘D,’ so I was only on academic probation. That first semester was hard. Maybe that was good; it made me more determined.”

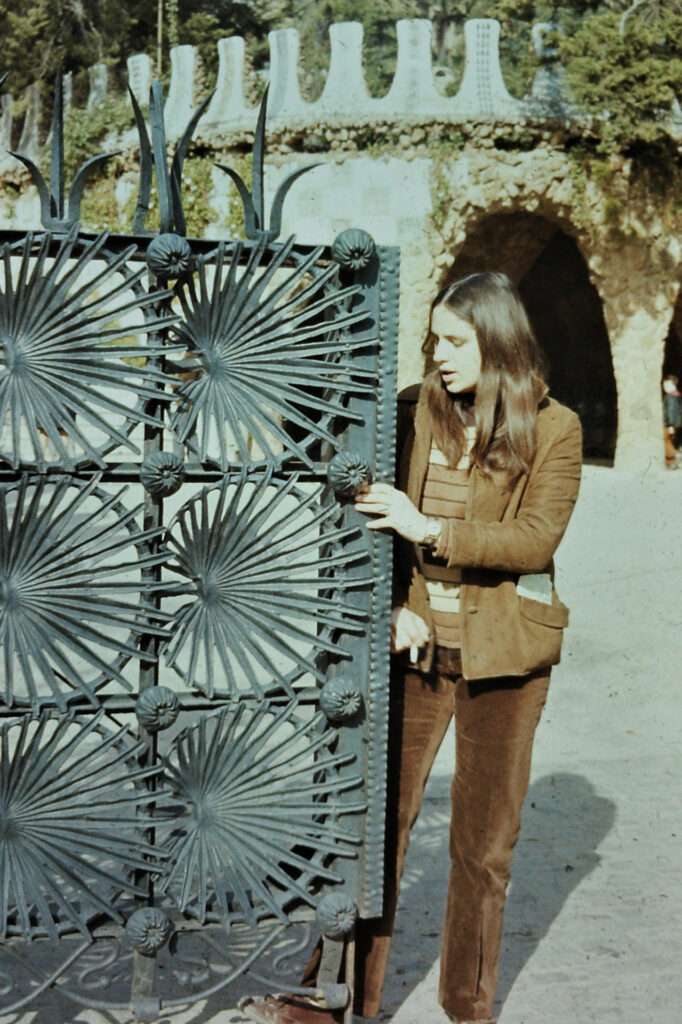

Jobs were scarce in 1971 when Carol was slated to graduate with a Bachelor of Architecture degree. Walking through the Illini Union one day, she picked up an application at a table hosted by a Peace Corps recruiter. Two weeks later she got a call asking if they could send her to Costa Rica. She went and worked there with a team of biologists, botanists, and planners designing the country’s new national parks.

It was a pivotal experience. First, she saw the power of an interdisciplinary team, which integrates multiple perspectives, including (one hopes) the community’s. Then, she learned about the importance of designing for environmental balance, or creating spaces that do no harm. She brought those ideas to the practice she runs today.

But first there was the challenge of getting a foot in the door of her profession back home. She returned to Chicago as a newlywed and searched for work. One place she interviewed looked at her credentials and then gave her a typing test. “Do architects need to know how to type?” she asked, puzzled. “No,” they told her. “But we thought you could sit at the reception desk during lunch and give the receptionist a break.” No job there.

She did eventually land a position at Holabird & Root, one of the oldest, most distinguished firms in Chicago. There she found a mentor in John Holabird, one of the partners, a man who had five daughters of his own. He took Carol under his wing.

“I’d go into John’s office where he was a pillar of support,” Carol says. “He was my friend until the last day.”

In 1974, Carol helped found Chicago Women in Architecture (CWA) and served as its first president. In 1981, she started her own architectural design practice with a classmate from the U of I. In 1997, she came to national attention when she was named lead designer for the new Oklahoma City Federal Building, to replace the one destroyed by a terrorist’s bomb in 1995. Then, in 2001, she won the commission to design Chicago’s Riverwalk.

“When we got that commission, people thought of the river as ugly and dirty,” says Carol. “The properties around it were ramshackle. Here is this world-class city with a derelict area right downtown. Yet the river is our heritage. It’s the reason the city is important. It’s why Chicago is here.”

The team went to work. Sixteen years and scores of awards later, the Riverwalk has become “Chicago’s living room”—one of its most popular and iconic spaces and a master class in urban design and engineering. Also highly satisfying to Carol is that it’s a place for the public, an environment in which to relax, eat, exercise, hang out, or seek a contemplative moment in the heart of the city—in short, to be human.

Today, she is also passing on what she knows to architecture students at Illinois Institute of Technology, where she’s taught an Advanced Design Studio for more than 30 years.

“I actually don’t think you can be a designer unless you’re an optimist,” Carol says. “Because if you’re a designer, you’re wedded to the idea of progressive change. Why design something if you’re not going to make it better?”

She thinks sometimes of her grandmother—the one she’s named for. At age 16, Carol’s grandmother came to America alone from the poorest part of Poland. At Ellis Island, you had to produce a letter from an American sponsor, and Carol’s grandmother did. But when she got to Chicago where the sponsor lived, the person who’d written the letter had left. Alone and starving, Carol’s grandmother got herself 90 miles down the road to LaSalle, Illinois, where another contact lived. She found work as a maid in a Polish boarding house and married one of the boarders within a year. They had nine children, one of whom became Carol’s father.

Carol shakes her head. “How do you do that?” she asks. “My grandmother was so brave. It’s such an American story.”

She considers her own journey, with its ups and downs. “I just feel lucky,” Carol adds. “I mean, architecture is hard. This has just not ever been easy. But I love it. This is what I was meant to do.”